Turing Test, Chinese Room, and Large Language Models

Last Updated on July 17, 2023 by Editorial Team

Author(s): Moshe Sipper, Ph.D.

Originally published on Towards AI.

The Turing Test is a classic idea within the field of AI. Originally called the imitation game, Alan Turing proposed this test in 1950, in his paper “Computing Machinery and Intelligence”. The goal of the test is to ascertain whether a machine exhibits intelligent behavior on par with (and perhaps indistinguishable from) that of a human.

The test goes like this: An interrogator (player C) sits alone in a room with a computer, which is connected to two other rooms — and players. Player A is a computer, and player B is a human. The interrogator's task is to determine which player — A or B — is a computer and which is a human. The interrogator is limited to typing questions on their computer and receiving written responses.

The test doesn’t delve into the workings of the players’ hardware or brain but seeks to test for intelligent behavior. Supposedly, an intelligent-enough computer will be able to pass itself off as a human.

The Turing Test has sparked much debate and controversy in the intervening years, and with current Large Language Models (LLMs) — such as ChatGPT — it might behoove us to place this test front and center.

Do LLMs pass the Turing Test?

Before tackling this question, I’d like to point out that we are creatures of Nature (something we forget at times), who got here by evolution through natural selection. This entails a whole bag of quirks that are due to our evolutionary history.

One such quirk is our quickness to assign agency to inanimate objects. Have you ever kicked your car and shouted at it, “Will you start already?!” And consider how many users of ChatGPT begin their prompt with “Please”. Why? It’s a program, after all, and I could not care less whether you prompted, “Please tell me who Alan Turing is?” or “Tell me who Alan Turing is”.

But that’s us. We wander the world ascribing all kinds of properties to various objects we encounter. Why? Basically, this probably had a survival boon, helping us to cope with nature.

In 1980, philosopher John Searle came up with an ingenious argument against the viability of the Turing Test as a gauge of intelligence. The Chinese room argument (Minds, brains, and programs) holds that a computer running a program can’t really have a mind or an understanding, no matter how intelligent or human-like its behavior.

Here’s how the argument goes: Suppose someone creates an AI — running on a computer — which behaves as if it understands Chinese (LLM maybe?).

The program takes Chinese characters as input, follows the computer code, and produces Chinese characters as output. And the computer does so in such a convincing manner that it passes the Turing Test with flying colors: people are convinced the computer is a live Chinese speaker. It’s got an answer for everything — in Chinese.

Searle asked: Does the machine really understand Chinese or is it simulating the ability to understand Chinese?

Hmm…

Now suppose I step into the room and replace the computer.

I assure you I do not speak Chinese (alas). But, I am given a book, which is basically the English version of the computer program (yeah, it’s a large book). I’m also given lots of scratch paper—and lots of pencils. There’s a slot in the door through which people can send me their questions, on sheets of paper, written in Chinese.

I process those Chinese characters according to the book of instructions I’ve got — it’ll take a while — but, ultimately, through a display of sheer patience, I provide an answer in Chinese, written on a piece of paper. I then send the reply out the slot.

The people outside the room are thinking, “Hey, the guy in there speaks Chinese.” Again — I most definitely do not.

Searle argued that there’s really no difference between me and the computer. We’re both just following a step-by-step manual, producing behavior that is interpreted as an intelligent conversation in Chinese. But neither I nor the computer really speak Chinese, let alone understand Chinese.

And without understanding, argued Searle, there’s no thinking going on. His ingenious argument gave rise to a heated debate: “Well, the whole system — I, book, pencils — understands Chinese”; “Disagree, the system is just a guy and a bunch of objects”; “But…”; and so on, and so on.

Today’s LLMs, such as ChatGPT, are extremely good at holding a conversation. Do they pass the Turing Test? That’s a matter of opinion, and I suspect said opinions run the gamut from “heck, no” to “Duh, of course”. My own limited experience with LLMs suggests that they’re close — but no cigar. At some point in the conversation, I usually realize it’s an AI, not a human.

But even if LLMs have passed the Turing Test, I still can’t help but think of Searle’s room.

I doubt what we’re seeing right now is an actual mind.

As for the future? I’d go with management consultant Peter Drucker, who quipped: “Trying to predict the future is like trying to drive down a country road at night with no lights while looking out the back window”.

(and if they do have an actual mind one day — it won’t be like ours…)

I See Dead People, or It’s Intelligence, Jim, But Not As We Know It

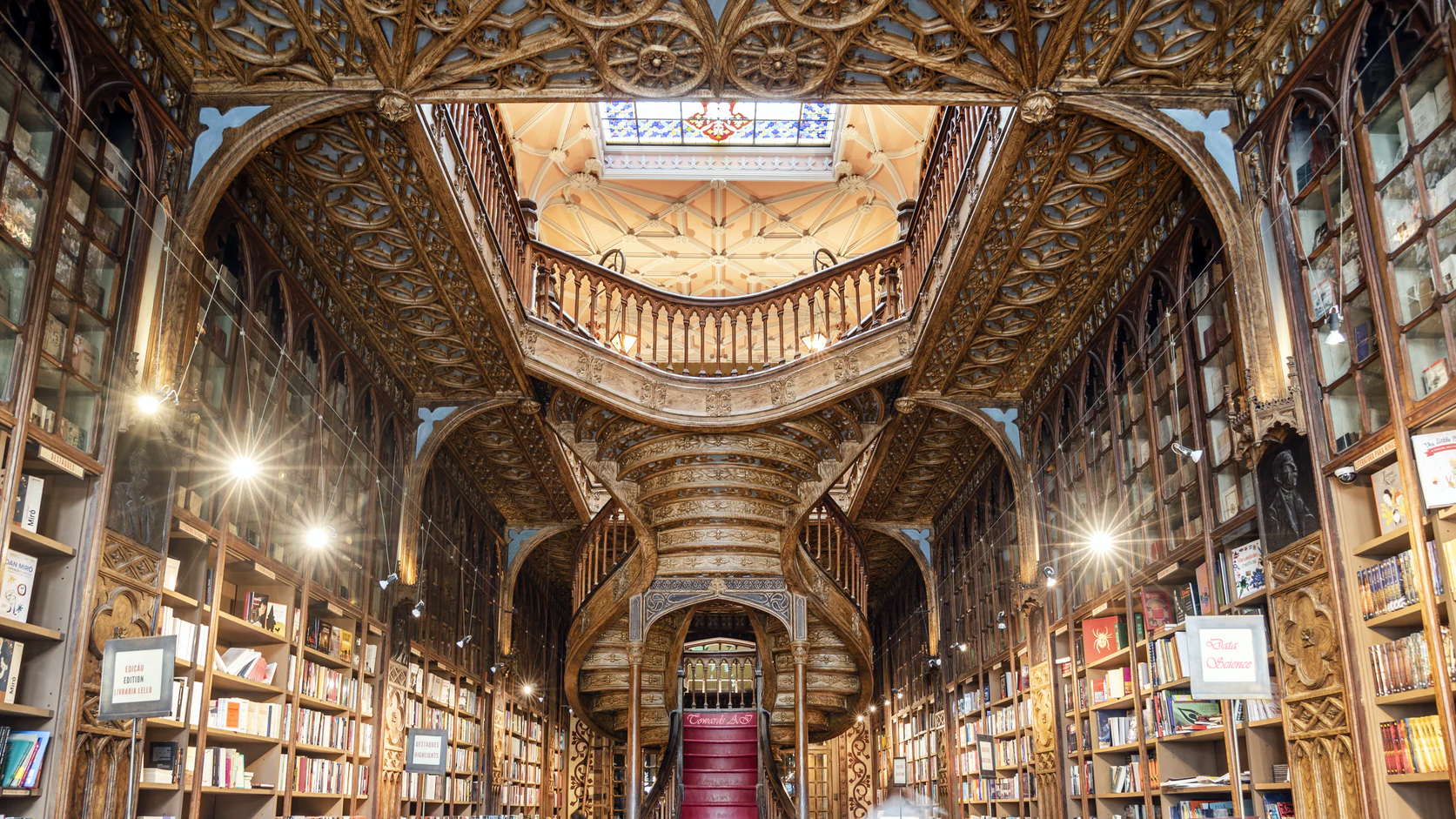

Take a look at this picture, the well-known painting “American Gothic” by Grant Wood:

medium.com

Join thousands of data leaders on the AI newsletter. Join over 80,000 subscribers and keep up to date with the latest developments in AI. From research to projects and ideas. If you are building an AI startup, an AI-related product, or a service, we invite you to consider becoming a sponsor.

Published via Towards AI

Take our 90+ lesson From Beginner to Advanced LLM Developer Certification: From choosing a project to deploying a working product this is the most comprehensive and practical LLM course out there!

Towards AI has published Building LLMs for Production—our 470+ page guide to mastering LLMs with practical projects and expert insights!

Discover Your Dream AI Career at Towards AI Jobs

Towards AI has built a jobs board tailored specifically to Machine Learning and Data Science Jobs and Skills. Our software searches for live AI jobs each hour, labels and categorises them and makes them easily searchable. Explore over 40,000 live jobs today with Towards AI Jobs!

Note: Content contains the views of the contributing authors and not Towards AI.