Paint, Pixels, and Plagiarism: The Rise of Generative AI and the Uncertain Future of Art

Last Updated on July 17, 2023 by Editorial Team

Author(s): Simba SHI

Originally published on Towards AI.

Pooping rainbows. This, according to Emad Mostaque — founder of Stable Diffusion and a leader in the AI art revolution — is the ultimate goal of artistic generative AI: to invigorate creativity among laypeople and empower anyone to “poop rainbows”, by producing extraordinary artwork that only requires simple inputs. Yet there is an ominous cloud behind this development. It was already clear that AI can challenge the limits of human cognitive capability (see AlphaGo’s impressive victory over the Go champion in 2016). Now, many fear that artistic creativity, which had previously been viewed as a uniquely human endeavor, is no longer immune.

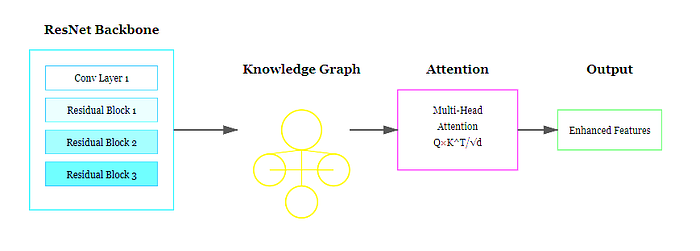

Generative AI technology, such as DALL-E and Midjourney, rely on “diffusion” models, which are fed with large datasets to discern patterns within images. These models are then able to generate new works that, while similar in style to their originals, ultimately appear distinct. This procedure raises obvious issues regarding intellectual property; the datasets used consist of information from across the Internet, many of which are copyrighted sources. In fact, Stable Diffusion’s image dataset even contains sensitive personal data, like medical records and private photos. Despite these issues, investors hardly seem troubled as Stability AI (Stable Diffusion’s parent company) announced in October 2022 that it raised a further US$101 million.

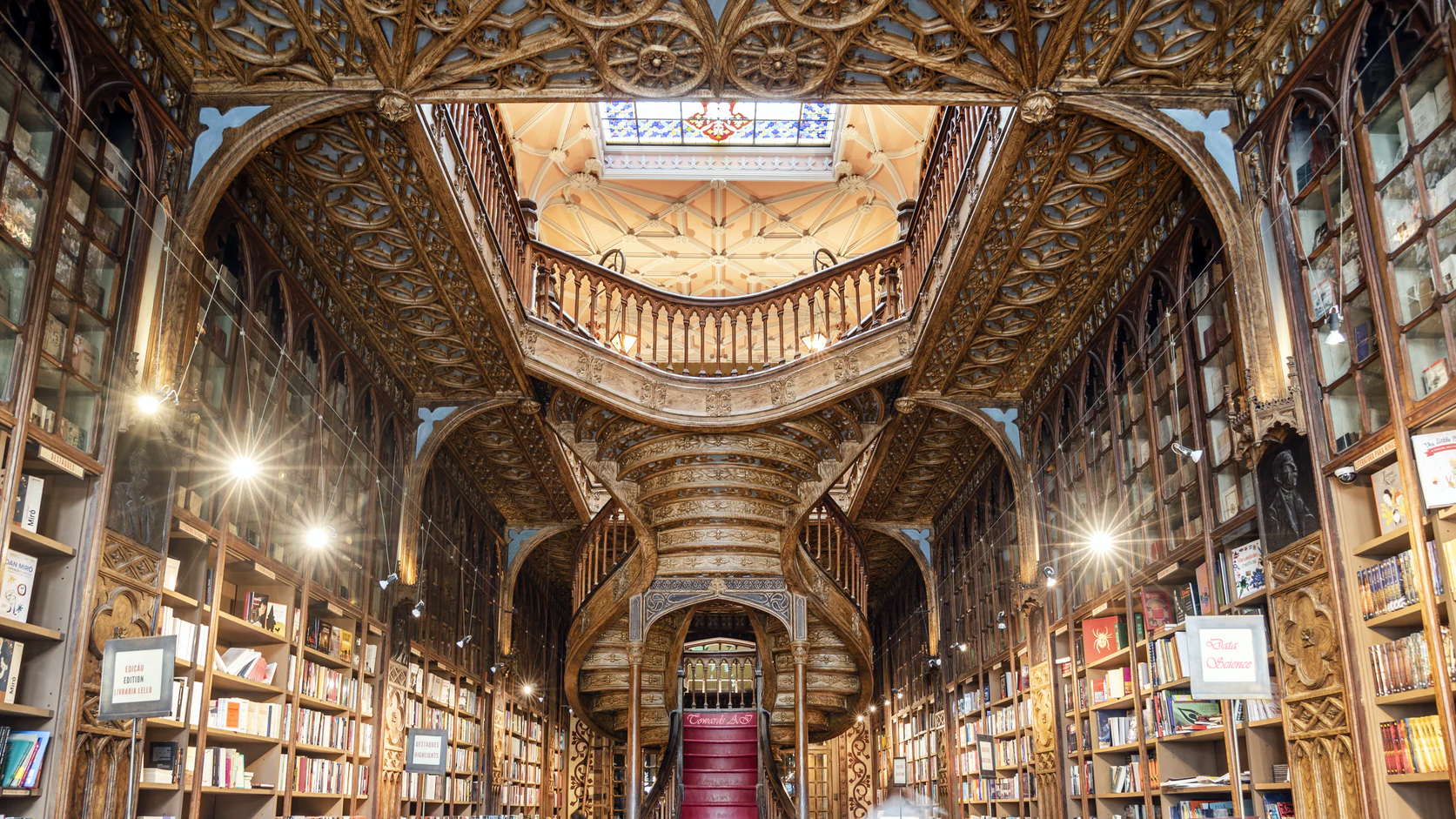

Generative AI firms are essentially stealing in order to strengthen their own models, which in turn might threaten the livelihoods of those from whom they steal. Specific artists’ styles are mapped into shallow doppelgangers and faux imitations, mimicking or blatantly plagiarizing the unique playfulness of manmade art. Compounding the problem is the ambiguity and the lack of law enforcement for “fair use” surrounding generative AI. The Texas Law Review claims that the use of copyrighted material is only justifiable in instances where the output differs so significantly from the original that it cannot be said to endanger the original owners’ market and audience share. It is clear that generative AI does directly interfere with market share by creating almost indistinguishable, free-riding works of art, as seen by AI-generated artwork winning the Colorado State Fair. This, in turn, devalues art as a whole and undercuts individual artists.

Furthermore, entire industries are at risk, such as those providing stock images used in illustrations for books, magazines, and online media. Companies have responded in mixed ways. Some are resorting to legal action; for instance, Getty Images has filed litigation against Stability AI for using millions of stock photos without their consent. Others are seeking compromise, like Shutterstock, which entered a collaborative deal with DALL-E to integrate AI into their product, perhaps out of fear of being eclipsed entirely.

The rise of generative AI is not the first time when new technology has rattled the creative class. Indeed, in past decades, tools like Photoshop and rotoscoping have accelerated publishing and replaced jobs. So, is generative AI an entirely novel threat? Examining two factors — rate of adoption and impact on novices within the industry — can help pose an answer.

While software like Photoshop requires a significant learning curve, products like DALL-E are instead designed to be accessible to the unskilled. Unsurprisingly, the rate of adoption is unprecedented, with DALL-E having reached a million users in only two months. Historically, new technologies have contributed to job creation and economic growth, albeit rendering certain jobs redundant in the process. Yet labor economists have pointed out how computer technologies create skill-biased technical change. This term suggests that automated tools accelerate productivity and enhance the wages of experienced workers, while simultaneously harming opportunities for lower-skilled employees whose jobs are far more repetitive and thus likely to be replaced. This phenomenon may raise the bar for entry into creative fields, discourage novices from considering artistic industries, and allow only an elite few to earn a living.

There have been recent efforts to protect artists against generative AI. One major advancement is the development of Glaze at the University of Chicago, a tool that obfuscates artworks to prevent AI scraping. The art itself, after being processed by Glaze, appears identical to the naked eye, yet is changed at the pixel level, which makes it unrecognizable to existing AI. Another such tool, Have I Been Trained, aids artists in examining whether their works have been included in the large dataset used to create Stable Diffusion. Through collaboration with Stability AI itself, the tool has resulted in the removal of over one billion artworks from Stable Diffusion’s dataset.

However, there are significant problems with both measures. Even Dr. Ben Zhao, Glaze’s creator, admitted it “does not guarantee protection” and that it is still possible to cheat the system. In the case of Have I Been Trained, the artistic flair of well-known artists already has inspired millions of non-AI works which replicate these artists’ styles, magnifying the chance of AI plagiarism because of the increasingly ubiquitous presence of those artists’ aesthetics. Not to mention that historical artists, such as Monet and Picasso, certainly will not be able to “opt out” their paintings any time soon.

The AI arms race over generative imaging means companies have few incentives to moderate the pace of development or adhere to high ethical standards. Thus, governments and policymakers must step in. Some regulatory policies have already been pursued, with the EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act leading the battle, followed by the White House releasing their “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights”, advocating an option for individuals to “opt out from automated systems in favor of a human alternative.” Despite these positive signs, regulations will take years to implement and even longer to enforce. Furthermore, these new policies focus primarily on large-scale AI used in critical infrastructure, rather than specifically protecting the intellectual property of artists.

While the necessary governmental regulations catch up (and they will, eventually), the reality may be that artists need to integrate generative AI into their workflow. Some artists are doing so already. For example, Mike Winkelmann (commonly known as Beeple) recently sold his AI-assisted NFT art for US$69 million, and the Oscar-winning movie “Everything Everywhere All at Once” was edited with help from AI. As more do, perhaps new positives and benefits will emerge.

Amidst warnings of AI posing a long-term “risk of extinction” for humankind, many (understandably) neglect the hazards it poses for human-created art. Generative AI’s unmatchable speed of creation and disregard for intellectual property poses an immediate risk to individual artists and large sectors of the creative industry. It also can dissuade promising artists from seeking a career since entry-level positions may be scarce and low-paid. Given that the exponential growth of this disruptive technology will not stop in the short term, those in the creative field will be forced to evolve; the winners will turn generative AI from foe to friend and adapt their workflow accordingly, while the losers may face extinction altogether.

(This article was not written by generative AI.)

Join thousands of data leaders on the AI newsletter. Join over 80,000 subscribers and keep up to date with the latest developments in AI. From research to projects and ideas. If you are building an AI startup, an AI-related product, or a service, we invite you to consider becoming a sponsor.

Published via Towards AI

Take our 90+ lesson From Beginner to Advanced LLM Developer Certification: From choosing a project to deploying a working product this is the most comprehensive and practical LLM course out there!

Towards AI has published Building LLMs for Production—our 470+ page guide to mastering LLMs with practical projects and expert insights!

Discover Your Dream AI Career at Towards AI Jobs

Towards AI has built a jobs board tailored specifically to Machine Learning and Data Science Jobs and Skills. Our software searches for live AI jobs each hour, labels and categorises them and makes them easily searchable. Explore over 40,000 live jobs today with Towards AI Jobs!

Note: Content contains the views of the contributing authors and not Towards AI.